LSU Partnerships Improve Hurricane Storm Surge Forecasts for Louisiana, Nation

December 02, 2020

UPDATE, September 1, 2021 — During Hurricane Ida, the CERA website got more than 20,000 public page views and 9,000 page views from pro users with a login. (For more updates, scroll to the bottom of this story.)

Ahead of Hurricane Ida and throughout last year’s record-breaking hurricane season, more people than ever turned to LSU’s Coastal Emergency Risk Assessment (CERA) tool, which visualizes storm surge predictions, to help protect communities and assets from flooding. The tool helps key decision-makers see where the water will go, and how high it will rise. By using CERA, they can be faster and more accurate in issuing evacuation orders and choosing where to position resources as well as when to open or close flood gates.

The Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA) and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers used LSU’s storm surge prediction visualization tool, CERA, to brief Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards (at head of table on left) ahead of Hurricane Ida making landfall near Port Fourchon on August 29, 2021. Mark Wingate, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers deputy district engineer for project management in New Orleans (in purple shirt on right), addressed the Hurricane Ida war room, while CPRA Executive Director Bren Haase pulled up the CERA website on his laptop (closest to camera).

“Nothing represents reality like reality,” said Windell Curole, general manager of the South Lafourche Levee District, as he watched the fifth named storm of the already record-breaking 2020 hurricane season make landfall in Louisiana with Hurricane Zeta last October 28. “As an emergency manager, you look for every piece of information at your disposal. And when you make your call—more than a day ahead of landfall—and you’re telling people to evacuate or open or close flood gates, you’d better be right.”

He understands the risks involved with basing decisions on guesstimates or telling people the wrong thing—they won’t evacuate when they should; whether it’s this time, if you don’t tell them to, or next time, if you tell them to evacuate and it turns out they didn’t need to.

“You can evacuate to naturally high ground to get away from the surge, but if you are not out in time, you can’t leave,” Curole said. “Greater danger and loss of life comes with storm surge, not wind.”

He and thousands of other emergency managers along the Gulf Coast and Atlantic Seaboard have come to rely on CERA, the Coastal Emergency Risk Assessment visualization tool developed at LSU, to help make some of their most difficult decisions in guarding local populations against storm surge. CERA, which relies on storm surge predictions computed by the ADCIRC surge guidance system (ASGS) developed in collaboration with the University of North Carolina, provides a quick visual interpretation of millions of computer data points to show flooding risks during a storm.

As Hurricane Eta zigzagged into the Gulf of Mexico about a week after Zeta and there was uncertainty about the storm’s track after it first devastated parts of Central America and then inundated Cuba and southern Florida, Curole sent LSU a straight-forward yet complicated question: What if Eta, instead of heading back across Florida as predicted, would come straight up across the Gulf of Mexico and hit Lafourche Parish? Then what?

Curole’s question reached Carola Kaiser, CERA lead developer and IT Consultant at LSU’s Center for Computation & Technology, or CCT, which houses seven servers that power CERA. She was fielding a record 243 new user login requests from across the nation, including the U.S. Coast Guard, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, FEMA, NASA, the U.S. Navy, the Department of Defense, the Department of Homeland Security, the Department of Transportation, the Department of Health & Human Services, several oil and gas companies, local and national law enforcement, media outlets such as The Washington Post and ProPublica, and around Louisiana—levee districts, the National Guard, the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA), and the Governor’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness (GOHSEP). She’d already established a White House Situation Room login.

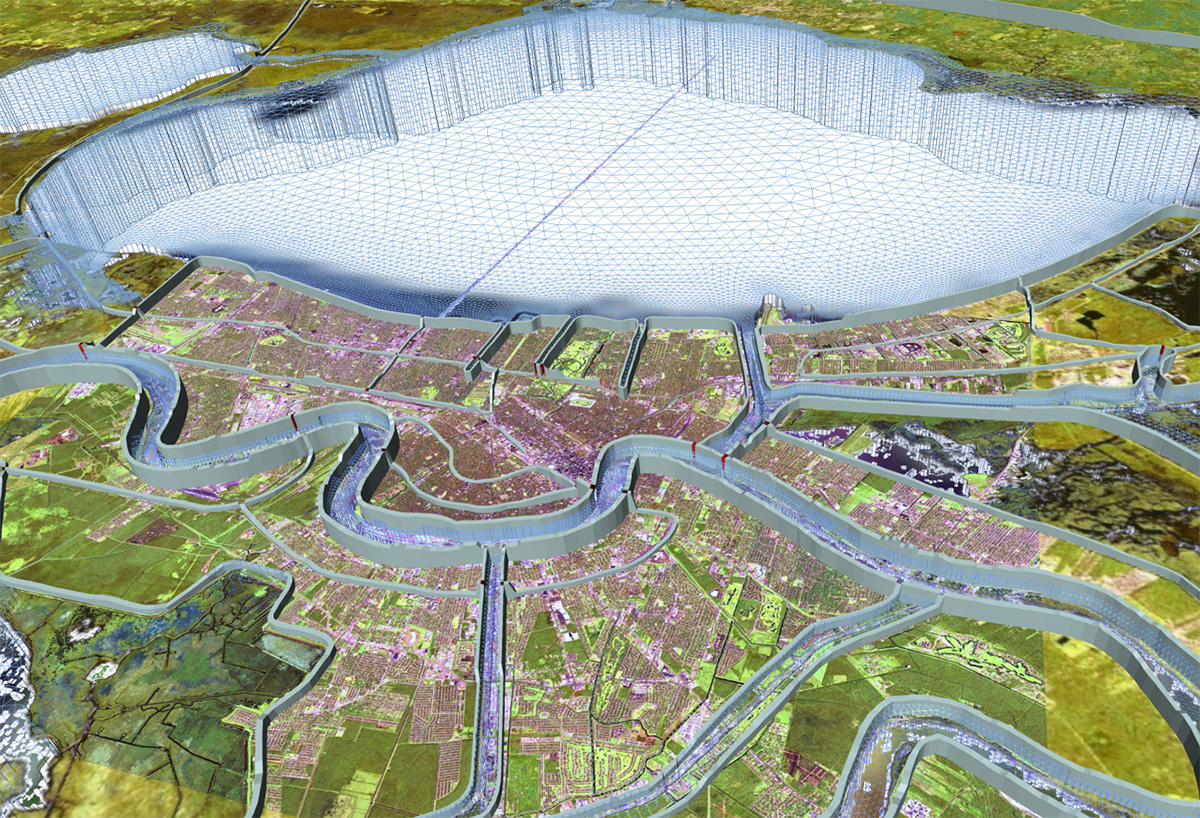

The need for better storm surge forecasting was made obvious after Hurricane Katrina, which flooded large parts of New Orleans. The LSU research effort grew from that and by public demand—emergency managers and planning commissions wanted not just federal levees on the map, but all structures that also happen to be in a constant state of change, requiring continuously updated measurements and local knowledge. To this end, LSU collaborates closely with the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA), which not only gathers on-the-ground data for the university-driven forecasting effort, but uses its output to advise tide and flood gate operators across the state. Above, New Orleans as seen through the three-dimentional mesh LSU is building along with its partners to help predict where the water will go.

What-if scenarios are an integral part of CERA for decision makers who can access layered maps in such high resolution they potentially show differences between neighboring houses. That information is not available to the general public at cera.coastalrisk.live, as that amount of detail easily could convey a false sense of certainty about what’s going to happen and what individual residents should do, which might contradict general area evacuation orders. Plus, predictions change. Every six hours, as the National Hurricane Center (NHC) issues its forecast advisories, ASGS recomputes all available flood level data, allowing CERA to update its maps within an hour or two, in time for critical briefings at every level.

A key recipient of this information in Louisiana is the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA). Since 2018, the CPRA has provided annual funding to LSU to support the overall forecasting efforts of CERA and ASGS. Their primary concern is the management of the intricate system of tide and flood gates throughout the state, as well as overseeing the complicated system of levees.

“The CERA tool is very important to CPRA—not only for operation of hurricane risk-reduction systems, but also for the prepositioning of flood-fighting assets,” said CPRA Operations Chief Ignacio Harrouch. “Keeping the model as up-to-date as possible is key, and this is why CPRA continuously collects and shares bathymetric and topographic data with LSU to facilitate continued improvement of the model.”

While Kaiser used to spend most of her time developing CERA, fixing bugs and adding new features, the balance between development and operations has shifted.

“Ten years ago, we had about eight months for development and four months when we responded to storms—mostly in July, August, September, and October,” Kaiser said. “This year, we started responding to named storms headed for the United States coastline on May 15, and we’re still responding. I don’t expect us to get more than four months for development before we’ll need to go back into operations again.”

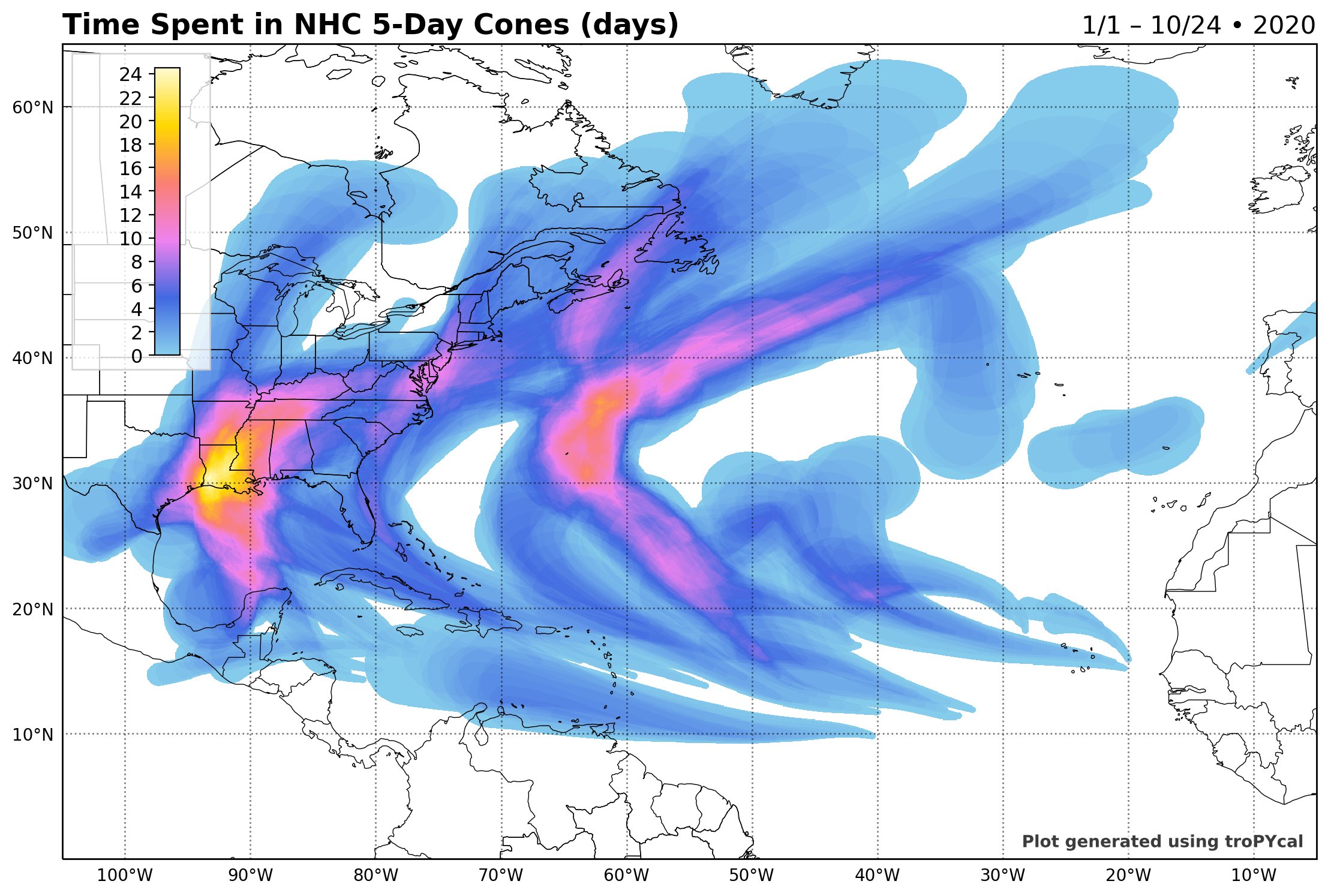

Louisiana has so far this year spent a total of three weeks “in the cone.” If you plot all of the five-day cones issued by the National Hurricane Center in 2020 on a map, Louisiana lights up like the center of a flame. While the official Atlantic hurricane season spans June 1 to November 30, tropical storms no longer come as a surprise when they form outside this window.

“This year, I’ve actually compared what we do with the firefighters in California who usually spend part of their time doing land management and part of their time fighting fires but now have no time to do land management because they’re fighting fires all the time,” said Jason Fleming, a consultant who collaborates with Kaiser on the software automation system, ASGS, which produces results for CERA.

If CERA is like the dashboard and GPS navigation system of a car, ASGS is the steering wheel and the pedals while ADCIRC is the motor under the hood—a command-line Fortran program that outputs raw data.

When the amount of time spent “in the cone” in 2020 is plotted on a map, Louisiana lights up like the center of a flame. Graphic courtesy of Sam Lillo @splillo.

“ADCIRC can’t do the job by itself—ASGS enables large-scale production of tailor-made scenarios on supercomputers while CERA transforms the raw model results and maps them. And meanwhile, we’ve had one storm after another, then another, back-to-back. This leaves little time for code modifications or technical improvements while we’re always discovering new needs expressed by decision makers in the field,” Fleming added.

And yet, CERA added a new feature this year—logged-in users can now download some of the raw model data in a Geographic Information System (GIS) raster data format for rapid damage assessment or to feed their own models or studies. Usually, the analysis that follows each storm is more valuable in helping communities prepare for future storms than the forecasts.

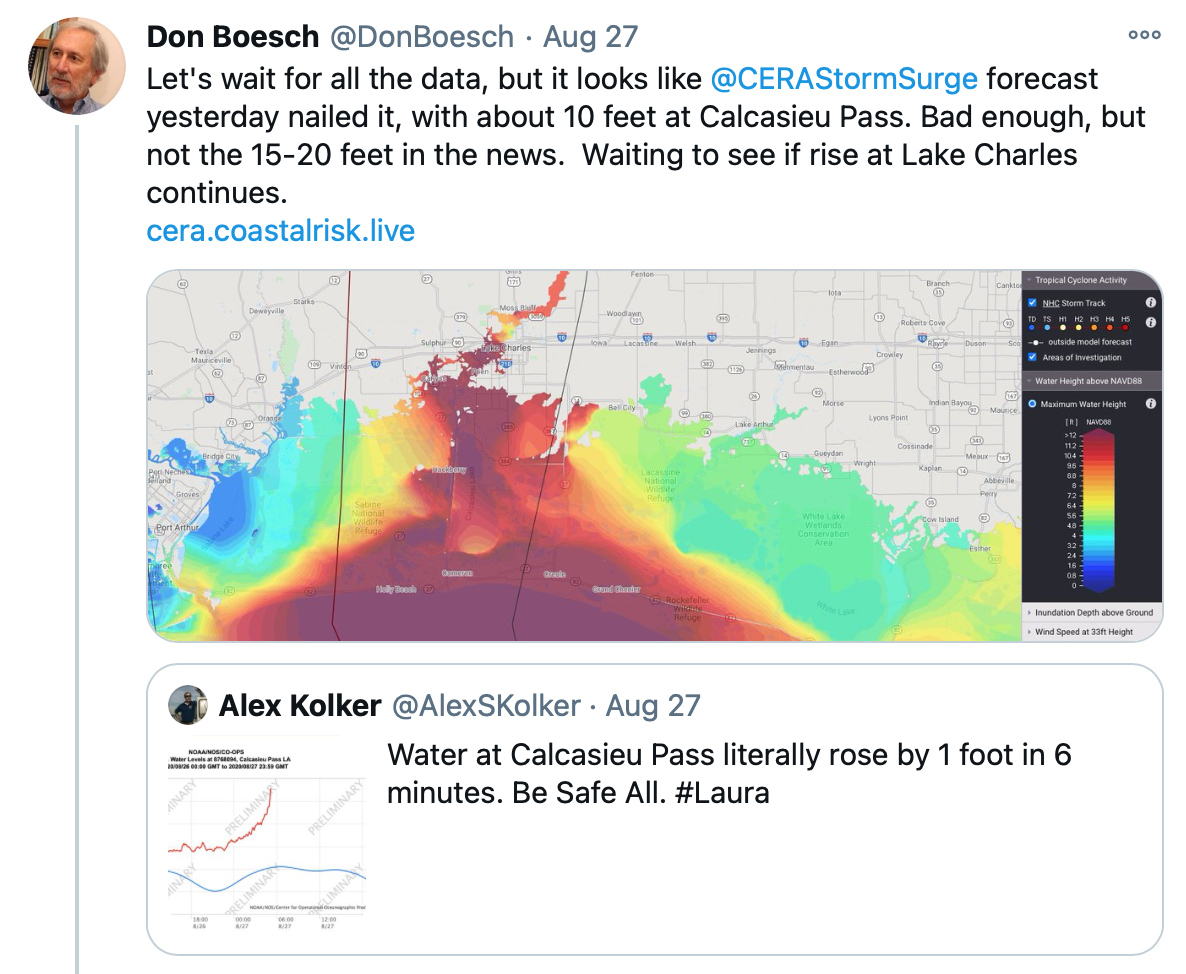

Last August, Hurricanes Laura and Marco broke another record—two hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico at the same time. While Laura rapidly intensified and made landfall in Creole, Louisiana as the strongest storm in history to hit the southwestern part of the state near the Texas border, Marco weakened. This didn’t relieve the CERA team, however, which was coordinating with the governors of both Louisiana and Texas at the same time, issuing flood maps well ahead of landfall and breaking its seasonal record as far as unique users of the CERA website—10,223 in eight days.

CCT and Louisiana Sea Grant, which supports Kaiser’s and Fleming’s work, have been driving forces behind the development and operation of CERA since the beginning.

“For Hurricane Laura, ADCIRC and CERA were actually running +20% scenarios for possible increases in wind intensity while the event was happening,” said Louisiana Sea Grant Director Robert Twilley. “Also, alternate scenarios for the storm moving either to the east or to the west. ‘If the storm shifts, this is what you’re going to see.’ Nothing can touch that.”

Advisories issued by the National Hurricane Center, meanwhile, don’t include alternate tracks—only the most likely outcome. While the government entities in charge of public safety initially had concerns about CERA competing with their own guidance, those worries appear to have ebbed. A recent broadcast email from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) ahead of Hurricane Delta last month read, “If you live in a coastal zone, the NHC, NWS, NOAA, and CERA have tools to predict storm surge and help you prepare.” The acronym NWS stands for the National Weather Service, and both NHC and NWS fall under NOAA.

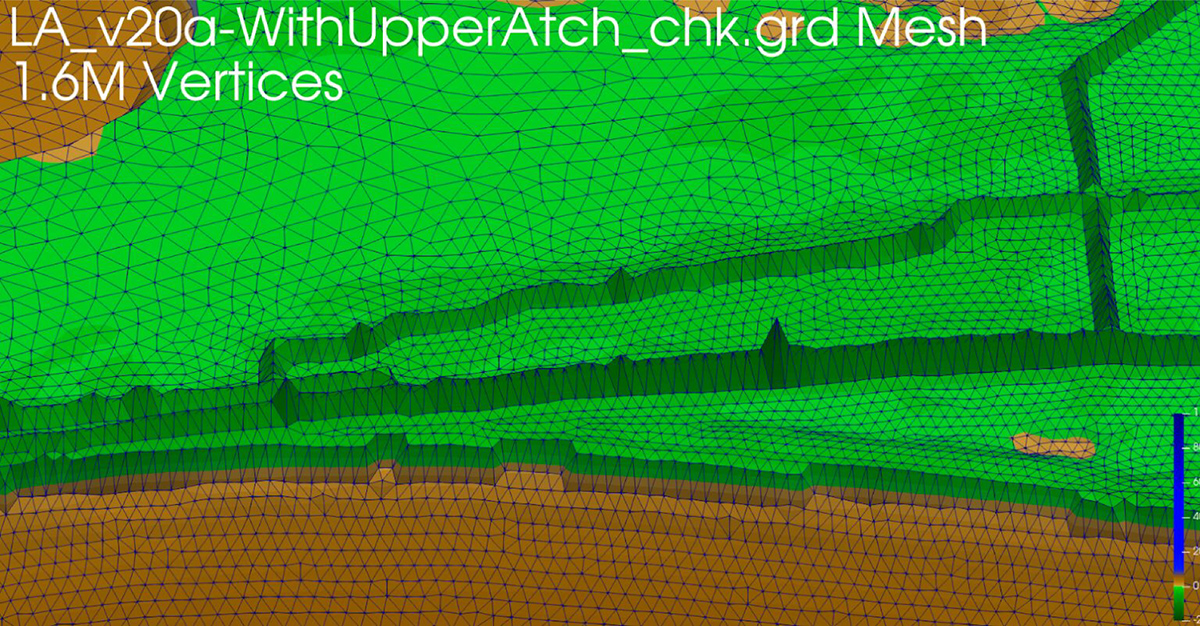

The ADCIRC mesh contains millions of vertices to describe the land form, both below and above the water surface. This picture shows the area near Creole, Louisiana where Hurricane Laura made landfall as the strongest storm in history to hit the southwestern part of the state. “The uniqueness of our coast demands higher research capacity building—our challenges are greater and therefore our research capacity has to be greater,” said Louisiana Sea Grant Director Robert Twilley, a long-time supporter of the ADCIRC and CERA storm surge forecasting systems.

Twilley was the associate vice chancellor of research at LSU after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and in the room when then-director of the National Weather Service office in Slidell (now director of the National Hurricane Center) Ken Graham came to campus as the university was organizing a series of Grand Challenges to leverage its research capacity to help the people of Louisiana—which is what CERA grew out of. Hurricane Katrina had brought the risks of storm surge into the public consciousness. Forecasting storm surge, however, was a knotty problem—especially in Louisiana, which has the most complicated coast in the contiguous United States, with constant land loss due to storms and sea level rise (a horizontal motion) as well as subsidence, which is a general sinking of the land (a vertical motion), in combination with a complex system of hundreds of flood gates, pumps, and levees—some federal, some not. The multifaceted nature of that challenge alone required something like a major research university to help find solutions—especially in connecting federal agencies with thousands of local decision makers.

Someone else in the room that day was Curole.

“I looked at their federal storm surge map after Hurricane Katrina and it showed flooding in Lafourche Parish,” Curole recalled. “But we never flooded; our levee was successful. But since they don’t put any non-certified levee on a federal storm surge map, their map showed us flooded. If we’d called it a road, they’d put it on the map, but a levee, they did not. Meanwhile, everybody else flooded. Not us. It’s important to include all structures in surge modeling.”

“You have to understand—all flooding is local,” he continued. “And you have to mix the best technological information with real, on-the-ground information. You’ve got to bring in reality. Only that way can you turn knowledge into wisdom.”

Twilley remembers looking around the room at everyone’s faces when it became clear the Lafourche Parish levee “didn’t exist.”

“The silence of the people of Louisiana was astounding,” he said. “You can imagine what that did to the trust people had in the federal storm surge map. It became obvious at that point that we had to take care of ourselves and protect our own resources and people. The National Hurricane Center simply could not reach down to all of those people in Louisiana, like Windell Curole. Plus, it’s not NOAA’s job to protect Louisiana. It’s their job to protect the United States.”

The LSU Coastal Emergency Risk Assessment (CERA) website broke its seasonal record in visits for Hurricanes Laura and Marco, with 10,223 unique users. CERA offers different sets of information—general guidance to the public as well as high-resolution, fine-grained information to help local, state, and federal decision makers protect people and assets. “For the general public, we need to make the information as easy-to-understand and clear as possible, so we don’t give out any misguidance,” said lead CERA developer Carola Kaiser.

It took several years for emergency managers in Louisiana to start putting their trust in CERA, too. Hurricane Isaac in 2012 was a turning point. About 7,000 (roughly half) of all homes in LaPlace, Louisiana flooded as a result of storm surge from the hurricane, which was predicted by the ADCIRC model and mapped on CERA. Yet, few people evacuated in time because no one else saw this coming. Flooding in LaPlace is especially problematic because that’s where the elevated I-10 interstate highway, one of the main evacuation routes out of New Orleans, dips down to ground level.

“LaPlace was on nobody’s radar screen, but it was on ours,” Twilley said. “The credibility that came with that storm really put CERA on the map. People realized that this is a tool that can give you insight into the unexpected. And how often do you not hear in Louisiana, ‘Well, I’ve never flooded…’ Well, guess what? The angle of each storm makes every storm unique, and we can’t rely on some probabilistic analysis of all storms in the past to estimate future risk. Instead, let’s talk about risk based on the storm that’s coming in right now—the unique aspects of the storm as its forming.”

Sometimes Kaiser and her colleagues cannot believe what they see on CERA’s maps either—unexpected patterns are their cue to delve into the details and make sure the outcome isn’t due to a glitch of some kind. As the monster storm Laura was about to make landfall near Lake Charles, Louisiana and the map turned dark red from predicted flooding, there was a clear spot right on the coast.

“‘This looks unusual,’ we said, but it turned out to be correct because the highways there acted like a barrier and spared an area,” Kaiser said.

The calculations for ADCIRC and CERA rely on several supercomputers and servers at geographically distributed supercomputing centers. The main burden is carried by LSU (SuperMIC) with CCT (CERA servers) and the Louisiana Optical Network Initiative, or LONI (Queenbee2, Queenbee3), where the supercomputers are managed by Sam White. An integral partner is University of Texas at Austin’s Texas Advanced Computing Center, or TACC (Frontera, Stampede2), and the project also relies on critical resources at the Renaissance Computing Institute, or RENCI, at University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill. Co-developers of the ADCIRC model framework are Rick Luettich, director of the Department of Homeland Security Coastal Resilience Center at UNC Chapel Hill, Joannes Westerink of Notre Dame, and Clint Dawson at University of Texas at Austin.

Often, the same calculations are run on different supercomputers in separate states, in case one fails.

“If they’re holding a briefing at 6 a.m. to make a decision about emergency operations and the advisory with the updated storm track comes out at 4 a.m., we have to turn that around really quickly,” Fleming said. “Reliability is everything. If we give them an answer that’s dead-on accurate but two hours late, it’s useless. We might just as well have done nothing.”

CERA’s storm surge predictions for Hurricane Zeta were confirmed by hundreds of users on the ground. Here, a backyard deck in Ocean Springs, Mississippi turns into a dock.

The computations are so demanding it would take about a week to run a single scenario on a home computer. Better storm surge forecasting and high-performance computing have therefore grown hand in hand at LSU, one entirely reliant on the other. But it’s about much more than computer science, Twilley is quick to point out.

“You can run code on a computer, but if you don’t know what the results mean because you don’t understand the connections between the physics, oceanography, and the data, well, it’s almost dangerous, if I’m honest,” Twilley said. “This is why we dedicated the Louisiana Sea Grant Laborde Chair to hurricane storm surge forecasting research, which allowed LSU to hire Scott Hagen in 2015.”

The arrival of Hagen as director of the LSU Center for Coastal Resiliency and his then-Ph.D. student, Matthew Bilskie, led to annual enhancements of the existing ADCIRC mesh for the coastal land-margin of Louisiana, and the development of ADCIRC real-time forecasting models for Mississippi, Alabama, and the entire west coast of Florida.

“It’s all about how the computer ‘sees’ the land,” Hagen explained before his recent passing. “We include enough computational points to model the flow of water from the continental shelf, into the channels and bays, over the marshes and onto the upland regions right up to the levees, hopefully not seeing levees overtopped. It’s about depth and surface characteristics, the parameters that describe resistance to the flow of water and help describe how the wind interacts with the water flow as well.”

The CPRA leads the development of the Coastal Master Plan for Louisiana and collects and continuously updates the elevation data for land and levees as well as for water depth that ADCIRC and CERA rely on.

“The CPRA is a most valued partner,” Hagen continued. “In fact, part of our success here at LSU has been building partnerships. This comes back to what it means to be a research university and serve the state. Most importantly, we educate students, but it takes a people connector such as LSU to make something like this happen.”

One of Hagen’s former students, Matthew Bilskie, now an assistant professor at the University of Georgia, graduated from LSU in 2016 with a Distinguished Dissertation Award. He still works closely with Hagen on updating the ADCIRC model mesh and leads the development of the slide decks provided to key decision makers.

“The slide decks show when we can expect peak water levels to occur,” Bilskie explained. “This is important to the state of Louisiana for tide and flood gate operation. Many floodgates have water level ‘triggers,’ or thresholds, whereby a flood gate must be closed. The slide decks and model forecasts can provide guidance on when and where flood gates should close and then re-open, after a storm has passed.

During the record-breaking 2020 hurricane season, first responders, including the Louisiana National Guard, relied on CERA to help guide teams, equipment, and supplies into position—as close to the events as possible, but out of harm’s way.

“The storm surge map helped me pre-position the right types of equipment for a windstorm versus a flooding event,” said Colonel St. Romain, commander of Louisiana National Guard’s 225th Engineer Brigade, about responding to Hurricane Laura in the Lake Charles area in a recent interview for the Esri Blog. “We have high-water vehicles, we have boat systems, and we have engineering equipment to clear roads so emergency vehicles and power companies can access impacted areas.”

LSU’s storm surge guidance continues to help decision makers prioritize where to deploy critical yet limited resources, whether that’s truckloads of ice, equipment to clear debris, or manpower to secure surface and underground chemical storage tanks, which there are quite a few of in Louisiana—essentially, where to go first.

“There is no information center you can call that tells you the answer to that question,” Hagen said. “What our modeling does is help decision makers look beyond what’s obvious.”

Twilley nodded in agreement:

“And you might not hear about any of this in the news, because when the right decision is made and disaster is avoided, it becomes non-news. But it’s really important stuff.”

Storm surge forecasting can also assist with long-term planning to help make communities safe and whole. In a recent paper—written by another of Hagen’s Ph.D. students, Chris Siverd, along with Hagen, Bilskie, Twilley, and others—the researchers discussed the costs associated with protecting the area of Lafitte, Louisiana from flooding up until 2110 in comparison with the expected cost of securing New Orleans and other more densely populated areas.

Much of their research stems from needs expressed by people on the ground—those who ultimately will use and benefit from the findings, such as the residents of Lafitte. In refining CERA and the different ways storm surge guidance is communicated to users, the researchers conduct focus groups with people such as Curole to listen to their needs and make sure they speak the same language.

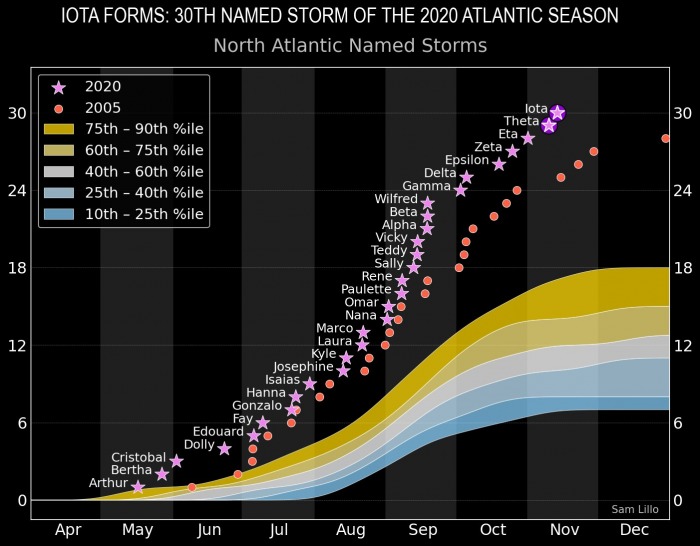

Thirty named storms: 2020 is the only season that has seen two major hurricanes (meaning, Category 3 storms or higher) in November in Hurricanes Eta and Iota. Graphic courtesy of Sam Lillo.

To this end, the LSU team has continued to grow and now includes Denise DeLorme, professor of environmental communication, and Paul Miller, assistant professor of coastal meteorology, both in the LSU College of the Coast & Environment.

“The transdisciplinary aspect of our work goes beyond what you’d think of interdisciplinary research, bringing in experts from diverse fields,” Hagen said. “We take it a step further and involve the stakeholders, such as the CPRA and their flood gate operators.”

In this way, Hagen argued, large research universities are uniquely well situated to tackle the complex challenges brought on by a constantly changing environment. Through its extension services and physical presence in every parish in Louisiana, LSU can work with public and private stakeholders as well as federal agencies.

“What I will never forget,” said Twilley, thinking back to that day after Hurricane Katrina when decision makers from several agencies gathered to identify critical research needs for the state of Louisiana, “is that the first person that spoke was Pat Santos, who was the head of the Governor’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Protection at the time. He got up and blew that place away. He showed us the timeline of every decision he makes, and said, ‘I don’t care what your modeling does—if it doesn’t help me with my timeline, it’s not worth a pfft.’ From that point on, our challenge was to build the operations piece to have detailed and accurate forecasting models available in time for local decisionmakers to be able to protect assets, infrastructure, and people. We had to make sure that what we put out served Pat Santos, and others like him.”

Last summer, 30 emergency managers from Texas followed by 50 emergency managers from across the nation participated in LSU workshops to get trained on how to use the more detailed aspects of CERA. Outreach will remain a central component of the LSU effort, said Kaiser:

“Without visualization or communication, if no one sees or uses your results, you just have huge piles of numbers.”

Storms Laura and Marco brought two hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico at the same time. They had emergency response teams in both Texas and Louisiana on high alert, and the LSU storm surge forecasting team coordinated with both governors to help protect people and assets.

September 1, 2021 UPDATE, cont.—New for this year, CERA is adding and integrating a new model called the Compound Flood Inundation Guidance System (CFIGS), developed by hydrologist Katelyn Costanza of CE Hydro, a small, woman-owned, Louisiana company. From now on, CERA pro users will be able to see not just the water being pushed inland from the coast by storms (wind-driven surge), but also inland-to-coast flooding caused by rainfall from not just hurricanes, but any large storm. It will include impacts on structures, to help disaster managers further safeguard critical infrastructure and allow for more detailed planning.

“Before starting my own company, I worked for the National Weather Service and the Army Corps of Engineers for 15 years with a focus on floodplain management and flood inundation mapping,” Costanza said. “Areas that received the combined impacts from storm surge and rainfall were the most challenging, so after starting my company, I wanted to focus on providing flood guidance in these areas. We used CERA guidance while at the National Weather Service, in addition to official storm surge forecasts provided by the National Hurricane Center. We got familiar with and trusted CERA, and that’s why it was important to me that we now collaborate.”

So far, CFIGS is primarily developed for the Lake Pontchartrain Drainage Basin, where rivers starting in Mississippi drain into Lake Maurepas and Lake Pontchartrain. But through ongoing collaboration between Costanza, CERA, and the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA), the service area should soon expand.

Another new capability for the 2021 hurricane season is that pro users now can download data in a widely used format known as GeoTIFF, making it easier for them to take the CERA data and run their own calculations on their own platforms. Users can click on any CERA map point and pull up graphs to show surge forecasts for that particular place. In addition, CERA is “going global” this year by integrating a new National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) model for storm surge that covers the entire world, the Extratropical Surge and Tide Operational Forecast System (ESTOFS).

Note: The LSU Center for GeoInformatics (C4G) supplies data to all partners in this project, including the CPRA, USACE, DOTD, and the South Lafourche Levee District.

In Back-to-Back Hurricanes, Louisiana National Guard Calls on Predictive Model (Esri Blog)

ERDC researchers use numerical modeling to assist with hurricane preparations

CPRA Awards Storm Modeling Contract to LSU Center for Coastal Resiliency

LSU Professor Explores Possible Impact of Flooding With Storm Surge

Stakeholder Focus Groups Improve Communication of Coastal Sea Level Rise Risks